Have you ever heard of the Golden Number? The Divine Proportion? Nature's greatest secret, the deepest mystery on earth, and the world's most astonishing number? No? Well, it might be the second most hyped number after Pi, and it's the subject of such things as this website, this video, and this book. If you believe these sources, then the Golden Number (or Phi) is a mysterious value with strange properties that appears in random places and dictates the rules of all of human civilization and perhaps all of the entire universe as well.

Then, there's The Golden Ratio, a book about Phi which tries to dispel some of the mystique around it. Not all of the mystique, but some of it. It addresses both the mathematical properties of Phi (like its connection with Fibonacci numbers) and the more wiggly properties of Phi (like its use in art as a standard for beauty). I think it does a good job of remaining mostly impartial, denying claims which are probably not true (like that the egyptians built the pyramids using Phi) and verifying claims that are true (such as Phi's prevalence in art after Luca's book The Divine Proportion).

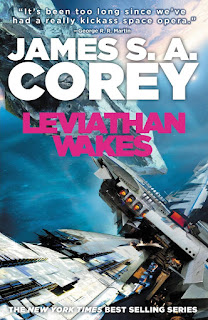

So, if you're looking at all the hype and thinking to yourself wait but no that's not how the universe works, then you might want to give The Golden Ratio a read. And, if you're totally a Phi fanatic, you might want to read it too, just to see what the fuss is about. And, if you've never even heard of this number before, then you can go read something else. I hear Leviathan Wakes is pretty cool.

P.S. One problem is that it doesn't quite explain all of the mathematics in an intuitive way. If only someone were to do that, possibly in some sort of visual episodic format. Alas, that will likely never happen.

Wednesday, July 19, 2017

Tuesday, July 18, 2017

Caliban's War (The Expanse book 2)

Caliban's War is the second book in the Expanse series. It's still the future, and everything is mostly fine as long as you don't think about Venus so don't think about Venus. The three superpowers (Earth, Mars, and the Belt) are eyeing each other nervously. As long as nobody rocks the boat, and Venus stays quiet, it looks like things will go back to normal soon.

Bobbie Draper is working on Ganymede, a moon where scientists do farming. She's in the Martian military, and her job is to stare at the Earth military while farming happens. Because, seriously, who would attack a farm moon? Then a lanky humanoid with huge hands and a huge head rips through both teams and violently explodes. Bobbie is the only survivor. Now, she's got one thing on her mind: revenge. And also I think she has PTSD.

But, she wasn't the only person on Ganymede. There was also Praxidike Meng, or "Prax," one of the aforementioned farm scientists. Now his science farm has been destroyed, along with most of his life's work. At least he still has his daughter,Amy or somethingMei, who was kidnapped shortly before the monster appeared so okay maybe he doesn't have his daughter. Still, he has a slim hope of finding her, so that's what he'll do.

Back on Earth, Chrisjen Avasarala is hard at work as a politician trying to keep the solar system falling apart. Then this whole Ganymede business happens, and things start really getting bad. Also, Venus seems to be acting up a bit. Try not to think about it. Anyways, she's got to put all the pieces together and figure out who done the monster, and also make some friends.

And James Holden is still there, with his crew, trying to deal with things as best he can. He messes up slightly less in this one. I think he's learning.

So, to be honest, I liked the original book better than this one. First of all, Leviathan Wakes straight-up had more action, and I like my boom boom bang. Second, I feel like only having two main characters, rather than the four in Caliban's War, kept things simpler and more predictable, which I felt was a good thing. There's no character order in Caliban's War, so it sometimes just flips between two characters without addressing the other two, which lessens a bit the feeling of everything is going wrong everywhere.

Still, Caliban's War is a good book, and the new characters are all nice. If you liked Leviathan Wakes, you'll probably like it. Yep, that's my big final rating: "If you liked the first one, you might want to continue the series." Don't I feel smart.

Bobbie Draper is working on Ganymede, a moon where scientists do farming. She's in the Martian military, and her job is to stare at the Earth military while farming happens. Because, seriously, who would attack a farm moon? Then a lanky humanoid with huge hands and a huge head rips through both teams and violently explodes. Bobbie is the only survivor. Now, she's got one thing on her mind: revenge. And also I think she has PTSD.

But, she wasn't the only person on Ganymede. There was also Praxidike Meng, or "Prax," one of the aforementioned farm scientists. Now his science farm has been destroyed, along with most of his life's work. At least he still has his daughter,

Back on Earth, Chrisjen Avasarala is hard at work as a politician trying to keep the solar system falling apart. Then this whole Ganymede business happens, and things start really getting bad. Also, Venus seems to be acting up a bit. Try not to think about it. Anyways, she's got to put all the pieces together and figure out who done the monster, and also make some friends.

And James Holden is still there, with his crew, trying to deal with things as best he can. He messes up slightly less in this one. I think he's learning.

So, to be honest, I liked the original book better than this one. First of all, Leviathan Wakes straight-up had more action, and I like my boom boom bang. Second, I feel like only having two main characters, rather than the four in Caliban's War, kept things simpler and more predictable, which I felt was a good thing. There's no character order in Caliban's War, so it sometimes just flips between two characters without addressing the other two, which lessens a bit the feeling of everything is going wrong everywhere.

Still, Caliban's War is a good book, and the new characters are all nice. If you liked Leviathan Wakes, you'll probably like it. Yep, that's my big final rating: "If you liked the first one, you might want to continue the series." Don't I feel smart.

Labels:

cryptids/monsters,

flying machines,

friendship,

future,

series,

suspense,

technology,

zombies

Friday, July 07, 2017

Math for Mystics

Math for Mystics is not really a book about math. It's written by Renna Shesso, a shamanic practitioner and priestess of wicca. It's about how to use vaguely mathy things when performing magical rituals and such.

As I have literally no experience in such things, I'm not sure how "good" the book is at what it does. The chapter on individual numbers was pretty cool, as was the chapter on magic squares and the one on days of the week. Unfortunately, I am almost certain to never use any of this in real life, so... I don't know what else to say.

If you're a wiccan or a druid and you want some... tips? I guess? Then buy Math for Mystics. You have my solemn word that it involves no serious mathematics. Otherwise, you can read, like, anything else.

As I have literally no experience in such things, I'm not sure how "good" the book is at what it does. The chapter on individual numbers was pretty cool, as was the chapter on magic squares and the one on days of the week. Unfortunately, I am almost certain to never use any of this in real life, so... I don't know what else to say.

If you're a wiccan or a druid and you want some... tips? I guess? Then buy Math for Mystics. You have my solemn word that it involves no serious mathematics. Otherwise, you can read, like, anything else.

Saturday, June 24, 2017

The Golden Section

The Golden Section, by Scott Olsen, is not worth your time. It's a book about Phi, the Golden Ratio, (1+√5)/2, 1.618033989ish, the "deepest mystery on earth." It explains none of the many properties of Phi that it presents, in the hopes of selling you on the mystery. Very little of what Olsen says is technically wrong, but it still leaves my with a kind of snake-oil salesman feeling. Of course, it does have pretty pictures, and it's over quick, so that's something. It also has a nice iridescent title.

If you want a small book full of pretty pictures and snake oil, along with some references to actual mathematics, then The Golden Section will do nicely. If you don't want that, then try anything else.

P.S. Man, if only someone would make like a cool series of videos explaining the properties of Phi so that it would seem less mysterious and people wouldn't fall for the snake oil. That would be neat.

If you want a small book full of pretty pictures and snake oil, along with some references to actual mathematics, then The Golden Section will do nicely. If you don't want that, then try anything else.

P.S. Man, if only someone would make like a cool series of videos explaining the properties of Phi so that it would seem less mysterious and people wouldn't fall for the snake oil. That would be neat.

Friday, June 23, 2017

Leviathan Wakes (The Expanse book 1)

Space. The final frontier. Humanity, insatiable in its quest for exploration, tosses itself into the void between worlds, strapped to tin cans with high explosives. What could possibly go wrong? Well, James S. A. Corey (who is actually two people or something) aims to find out in Leviathan Wakes, the first book of a (planned) nine-book series.

Meet James Holden, executive officer on a freighter which brings ice between planets. The solar system is a big place, after all, and people still need water. Unfortunately, when responding to a mysterious distress beacon, the freighter is nuked and almost all of Holden's friends are killed. It's not pretty.

Let's see if Josephus Miller is doing any better. He's a detective on Ceres station, born and raised in the Belt. He's running into some trouble because his partner, Havelock, is from Earth, which means that Belters don't like him so much. Still, everything should be fine, as long as some Earther doesn't inadvertently start a war because someone nuked his freighter and almost all of his friends were killed. But what are the chances of that, am I right?

So, yeah, now a war is brewing. The Earth and Mars are looking at each other all shifty, and the Outer Planets Alliance which claims to represent the belt is making everyone a bit antsy. Also, there's that thing from the introduction which hasn't shown up in a while. Hope that's not important. Now Holden is on a mission to find out who killed his ship, and Miller is on a mission to find a lost girl named Julie, and... well, things get a bit hectic.

Leviathan Wakes is a bangin' book. It's got killer pacing, and characters that are interesting and fun to be with. The world seems real and realistic, even with the crazier things that show up. The tension and the stakes keep getting ramped up, with more and more people being dragged in, and then you remember the title is "Leviathan Wakes" and get really worried. To make things even more intense, we follow Holden and Miller in alternating chapters, so there's almost always a cliffhanger after each chapter even if you don't stop reading, which I think is a really cool way to do things.

If you like high-stakes space drama mystery action, or if you want to become lost in a world which might be about to lose itself, or if you want to get to know interesting characters which could all die at any moment, then you should read Leviathan Wakes. And probably the rest of The Expanse.

Meet James Holden, executive officer on a freighter which brings ice between planets. The solar system is a big place, after all, and people still need water. Unfortunately, when responding to a mysterious distress beacon, the freighter is nuked and almost all of Holden's friends are killed. It's not pretty.

Let's see if Josephus Miller is doing any better. He's a detective on Ceres station, born and raised in the Belt. He's running into some trouble because his partner, Havelock, is from Earth, which means that Belters don't like him so much. Still, everything should be fine, as long as some Earther doesn't inadvertently start a war because someone nuked his freighter and almost all of his friends were killed. But what are the chances of that, am I right?

So, yeah, now a war is brewing. The Earth and Mars are looking at each other all shifty, and the Outer Planets Alliance which claims to represent the belt is making everyone a bit antsy. Also, there's that thing from the introduction which hasn't shown up in a while. Hope that's not important. Now Holden is on a mission to find out who killed his ship, and Miller is on a mission to find a lost girl named Julie, and... well, things get a bit hectic.

Leviathan Wakes is a bangin' book. It's got killer pacing, and characters that are interesting and fun to be with. The world seems real and realistic, even with the crazier things that show up. The tension and the stakes keep getting ramped up, with more and more people being dragged in, and then you remember the title is "Leviathan Wakes" and get really worried. To make things even more intense, we follow Holden and Miller in alternating chapters, so there's almost always a cliffhanger after each chapter even if you don't stop reading, which I think is a really cool way to do things.

If you like high-stakes space drama mystery action, or if you want to become lost in a world which might be about to lose itself, or if you want to get to know interesting characters which could all die at any moment, then you should read Leviathan Wakes. And probably the rest of The Expanse.

Labels:

adventures,

cryptids/monsters,

detectives,

dying forever,

flying machines,

friendship,

future,

ghosts,

mystery,

series,

suspense,

technology

Thursday, June 01, 2017

The Irrationals

The Irrationals is not good. Don't read it. Okay fellas thanks for your time it's been fun I'll see you in the next review goodbye.

Still here? Huh. Strange. Well, I suppose I could give a bit more information. The Irrationals is written by Julian Havil, and is about the history of irrational numbers (the ones that aren't fractions). If you're not already a huge math person, you will definitely dislike The Irrationals, due to the sheer volume of proofs. Book is like 40% history and 60% proofs. And they've got some serious proofs in there, with elementary calculus and contradictions and the like.

If that was all The Irrationals was, it would be a fine book. A history of the idea of irrationality, including the first proofs that Pi and e are irrational, a proof that Phi is the "most irrational," and other neat goodies, along with some descriptions of what was happening at the time these proofs were discovered. It would be a book meant for math nerds, and as a math nerd I would have enjoyed it. Unfortunately, The Irrationals has another problem that is almost certainly a dealbreaker.

Sometimes, the book is just wrong. It's not that Havil is stating falsehoods, it's that there's sometimes just typos in important places. When reading The Irrationals, you not only have to understand the poorly-explained proofs, you also have to fix mistakes in the proofs so that they make sense. I think anyone who wasn't procrastinating on their review of All The Birds In The Sky would have a hard time getting to the end. I made a list of some of the more serious mistakes I saw, which I'll put in this document, but it'll still be a rough time. Unless you're some kind of math masochist (mathochist?), I recommend staying away from The Irrationals.

Still here? Huh. Strange. Well, I suppose I could give a bit more information. The Irrationals is written by Julian Havil, and is about the history of irrational numbers (the ones that aren't fractions). If you're not already a huge math person, you will definitely dislike The Irrationals, due to the sheer volume of proofs. Book is like 40% history and 60% proofs. And they've got some serious proofs in there, with elementary calculus and contradictions and the like.

If that was all The Irrationals was, it would be a fine book. A history of the idea of irrationality, including the first proofs that Pi and e are irrational, a proof that Phi is the "most irrational," and other neat goodies, along with some descriptions of what was happening at the time these proofs were discovered. It would be a book meant for math nerds, and as a math nerd I would have enjoyed it. Unfortunately, The Irrationals has another problem that is almost certainly a dealbreaker.

Sometimes, the book is just wrong. It's not that Havil is stating falsehoods, it's that there's sometimes just typos in important places. When reading The Irrationals, you not only have to understand the poorly-explained proofs, you also have to fix mistakes in the proofs so that they make sense. I think anyone who wasn't procrastinating on their review of All The Birds In The Sky would have a hard time getting to the end. I made a list of some of the more serious mistakes I saw, which I'll put in this document, but it'll still be a rough time. Unless you're some kind of math masochist (mathochist?), I recommend staying away from The Irrationals.

Friday, May 19, 2017

Scythe

It's the future. Everything is great. An incredibly powerful AI known only as the Thunderhead has taken over the world, and is hell-bent on making life good for everyone. There's no more war, no more poverty, no more disease, and no more death. With one exception.

The Scythes (pronounced SKITH-ees) are an organization of people who are tasked with keeping the population in check by killing ("gleaning") people. They are the most revered and feared members of society. Citra and Rowan are two of the minority of people who outwardly disapproves of the Scythes, which sucks for them, because a wise old Scythe named Faraday has appointed them as apprentices.

Now, Citra and Rowan have to compete with each other to see who gets to become a Scythe. Except, neither one actually wants the job. But they both kinda do. It's good fun. Also, there's this whole thing with these Scythes who are holding "mass gleanings," which are exactly as terrible as they sound. I hope those guys don't cause any trouble.

Neal Shusterman's Scythe is a pretty fun book. The story is a whirlwind, with mysteries that had me genuinely second-guessing myself throughout the book. Seeing the separate journeys of Citra and Rowan as they learn how to kill is cool. It's apparently the first book in a trilogy, but the ending is actually really satisfying, so it can stand entirely on its own. Scythe also pokes at some really interesting issues about death and longevity and utopia. If you like a bit of action, a bit of mystery, and a lot of murder, then you should pick up Scythe.

The Scythes (pronounced SKITH-ees) are an organization of people who are tasked with keeping the population in check by killing ("gleaning") people. They are the most revered and feared members of society. Citra and Rowan are two of the minority of people who outwardly disapproves of the Scythes, which sucks for them, because a wise old Scythe named Faraday has appointed them as apprentices.

Now, Citra and Rowan have to compete with each other to see who gets to become a Scythe. Except, neither one actually wants the job. But they both kinda do. It's good fun. Also, there's this whole thing with these Scythes who are holding "mass gleanings," which are exactly as terrible as they sound. I hope those guys don't cause any trouble.

Neal Shusterman's Scythe is a pretty fun book. The story is a whirlwind, with mysteries that had me genuinely second-guessing myself throughout the book. Seeing the separate journeys of Citra and Rowan as they learn how to kill is cool. It's apparently the first book in a trilogy, but the ending is actually really satisfying, so it can stand entirely on its own. Scythe also pokes at some really interesting issues about death and longevity and utopia. If you like a bit of action, a bit of mystery, and a lot of murder, then you should pick up Scythe.

Labels:

dying forever,

friendship,

future,

technology

Thursday, March 09, 2017

Logicomix

Logicomix is the story of the logician Bertrand Russell, as told by the man himself, as told by Apostolos Doxiadis and Christos H. Papadimitriou, drawn by Alecos Papadatos and Annie Di Donna. It is not a book about logic, or the history of logic, or how to live your life in the most logical manner. It really is a story about a real person, and I think it's really well done. For real.

The story follows Bertrand Russell from when he was a very small boy, and was still learning about how to see the world around him. Russell learns of the beauty and elegance in proofs, and sets off to try and prove all the things! This is the meat of the book, and it reads as thrilling a story as any.

This story is told via flashback, as Russell gives a talk to agitated peace protestors during World War II. This, in addition to letting Russell narrate, gives more direction to the story as a whole.

But Logicomix is not just that story. It also tells a part of the story of how Logicomix came to be, showing the day when Christos comes on board to help. Russell's story is presented with the authors and artists talking about what to include in the story. The whole layered narrative thing is fun, partly because so many people can interject, which colors the story just that little bit more. It is very well done.

So, if you think a story about searching for truth told through layered narratives sounds cool, then you should read Logicomix. And also I guess if you like logic or whatever. Or if you're curious about what logic even is, but don't want to actually do any of the hard stuff. Then this is a good book for you. Yep, I am happy with this paragraph's construction.

The story follows Bertrand Russell from when he was a very small boy, and was still learning about how to see the world around him. Russell learns of the beauty and elegance in proofs, and sets off to try and prove all the things! This is the meat of the book, and it reads as thrilling a story as any.

This story is told via flashback, as Russell gives a talk to agitated peace protestors during World War II. This, in addition to letting Russell narrate, gives more direction to the story as a whole.

But Logicomix is not just that story. It also tells a part of the story of how Logicomix came to be, showing the day when Christos comes on board to help. Russell's story is presented with the authors and artists talking about what to include in the story. The whole layered narrative thing is fun, partly because so many people can interject, which colors the story just that little bit more. It is very well done.

So, if you think a story about searching for truth told through layered narratives sounds cool, then you should read Logicomix. And also I guess if you like logic or whatever. Or if you're curious about what logic even is, but don't want to actually do any of the hard stuff. Then this is a good book for you. Yep, I am happy with this paragraph's construction.

Wednesday, March 01, 2017

The Mathematics of Various Entertaining Subjects

The Mathematics of Various Entertaining Subjects, edited by Jennifer Beineke and Jason Rosenhouse and written by a whole bunch of people, does not have an interesting title. I'd guess that, for the vast majority of people, the book is just as boring as it sounds. However, for math nerds like me, it's really interesting, and a fun introduction to how math is done in "the real world."

The Mathematics of Various Entertaining Subjects is a collection of 17 chapters, each written by different folks, and each about the some sort of game or puzzle. All of them (except maybe the first two) are heavy in mathematical language and notation. Some chapters explain the background really well, others not so much. I straight-up skipped a few of the chapters. The ones that I did read were, for the most part, very interesting. There's a lot of variety to the subjects of the chapters. One might go so far as to say that there are various entertaining subjects.

That's about as much as I can say without going into the individual subjects in depth. So, let's look at one of the subjects. I present to you the heart of my favorite chapter, lucky 13, by Maureen T. Carroll and Steven T. Dougherty. It's about tic-tac-toe on what are called "affine planes." The smallest interesting affine plane is this:

Tic-tac-toe is played on this plane the same way as on a normal one, but on this plane there are four extra lines (the big curvy ones). This looks complicated, but all that happens to tic-tac-toe is that four more winning arrangements are added:

These new four are the last ones on the bottom, and they make a sort of diagonal T-shape. Try getting together with a friend and seeing what this changes. I spent an entire period of Physics class messing with these, and had more fun than was probably warranted.

So, if you think you want to see some fancy math, most of which isn't presented for beginners, then read The Mathematics of Various Entertaining Subjects. If you don't, then don't. If you're not sure, then start with a friendlier math book. I've got a lot of them in the "numbers" tag now.

Have a good day and a great life. Peace!

The Mathematics of Various Entertaining Subjects is a collection of 17 chapters, each written by different folks, and each about the some sort of game or puzzle. All of them (except maybe the first two) are heavy in mathematical language and notation. Some chapters explain the background really well, others not so much. I straight-up skipped a few of the chapters. The ones that I did read were, for the most part, very interesting. There's a lot of variety to the subjects of the chapters. One might go so far as to say that there are various entertaining subjects.

That's about as much as I can say without going into the individual subjects in depth. So, let's look at one of the subjects. I present to you the heart of my favorite chapter, lucky 13, by Maureen T. Carroll and Steven T. Dougherty. It's about tic-tac-toe on what are called "affine planes." The smallest interesting affine plane is this:

Tic-tac-toe is played on this plane the same way as on a normal one, but on this plane there are four extra lines (the big curvy ones). This looks complicated, but all that happens to tic-tac-toe is that four more winning arrangements are added:

These new four are the last ones on the bottom, and they make a sort of diagonal T-shape. Try getting together with a friend and seeing what this changes. I spent an entire period of Physics class messing with these, and had more fun than was probably warranted.

So, if you think you want to see some fancy math, most of which isn't presented for beginners, then read The Mathematics of Various Entertaining Subjects. If you don't, then don't. If you're not sure, then start with a friendlier math book. I've got a lot of them in the "numbers" tag now.

Have a good day and a great life. Peace!

Wednesday, February 22, 2017

Zero

Zero is about nothing. By which I mean, it's about the idea of a void, a lack-of-thing, as being a sort of thing itself. It's written by Charles Seife, who also wrote Proofiness. Zero is similar to A Brief History of Infinity, by Brian Clegg, in that it's more of a history book than it is a math or science book. They're also similar because they talk about infinity, because zero is "infinity's twin."

The first six chapters of Zero (or the first seven, depending on how you count them) are about the idea of nothing slowly working its way into the mainstream, followed closely by the idea of the infinite. There was actually a lot of resistance to both of these ideas, especially in the West, which is made even more interesting by Seife's flowery writing. I'm not entirely sure what "flowery writing" actually means, but I'm pretty sure it happens in this book. Zero does technically go into some math, but never in much detail. There's just enough math to make sense of all the pretty pictures.

The last three chapters are about zero in physics, where it likes to cause problems. This second part seems much weaker than the first part; Seife uses quite a bit of hand-waving, and never shows us a single equation. I think that if Seife would show us the actual equations and where the zeros are, we would better understand why zero is to blame for these quirks. That said, I'm sure some people will be glad that the math all but disappears when the physics comes on.

If you wonder how ideas take hold, or like history, or are somewhat confused about zero yourself, then maybe give Zero a try. For what it's worth, I finished it in just three days, so it can't be all that boring. (Although, that probably says more about my schedule than it does about the book.) I think the best way to understand what Zero is like is probably just to read the introduction (which Seife calls "Chapter 0"), so I've just typed it up here. This might be illegal. Don't tell anyone. The point is, he remains that flowery throughout the book, and if you like that section, I think you can enjoy the rest.

The first six chapters of Zero (or the first seven, depending on how you count them) are about the idea of nothing slowly working its way into the mainstream, followed closely by the idea of the infinite. There was actually a lot of resistance to both of these ideas, especially in the West, which is made even more interesting by Seife's flowery writing. I'm not entirely sure what "flowery writing" actually means, but I'm pretty sure it happens in this book. Zero does technically go into some math, but never in much detail. There's just enough math to make sense of all the pretty pictures.

The last three chapters are about zero in physics, where it likes to cause problems. This second part seems much weaker than the first part; Seife uses quite a bit of hand-waving, and never shows us a single equation. I think that if Seife would show us the actual equations and where the zeros are, we would better understand why zero is to blame for these quirks. That said, I'm sure some people will be glad that the math all but disappears when the physics comes on.

If you wonder how ideas take hold, or like history, or are somewhat confused about zero yourself, then maybe give Zero a try. For what it's worth, I finished it in just three days, so it can't be all that boring. (Although, that probably says more about my schedule than it does about the book.) I think the best way to understand what Zero is like is probably just to read the introduction (which Seife calls "Chapter 0"), so I've just typed it up here. This might be illegal. Don't tell anyone. The point is, he remains that flowery throughout the book, and if you like that section, I think you can enjoy the rest.

Sunday, February 19, 2017

Flatterland

Flatterland is full of puns and science. Really, if it weren't for the name "Ian Stewart" on the front, I'd suspect it had somehow been written by me. Flatterland is a "sequel" of sorts to Edwin A. Abbott's Flatland, which I suppose you should technically read first, although I think Flatterland stands perfectly well on its own. Still, a quick review/summary of Flatland is in order.

Boop. Just did a quick review. Two paragraphs. It doesn't even have a picture of the cover. Go read it, if you'd like.

Anyways, back to Flatterland. As the tagline says, it's like Flatland, only more so. And with a healthy helping of Alice in Wonderland to boot. Flatterland is set about a hundred years after Flatland, and follows the adventures of Victoria "Vikki" Line, a woman who finds her some-number-of-greats-grandfather's book, which is entitled Flatland. (Yes, they are actually the same book.) Anyways, Vikki reads Flatland, and in it finds instructions for summoning a being from Spaceland, in a way that is kind of hilarious.

So, Vikki summons someone from Spaceland. However, she gets a bit more than she bargained for. Instead of the stuffy, boring old Sphere from Flatland, she meets a loud, energetic, grinning creature known as the Space Hopper, who can travel through much more than just stuffy, boring old Spaceland. The Space Hopper equips Vikki with a Virtual Unreality Engine, or VUE, and takes her on a tour of all sorts of spaces and geometries, meeting many strange people along the way. They pay special attention to a strange place called Planiturth, and the fact that its inhabitants don't really know which space they're in.

Personally, I really liked Flatterland. I'm a big fan of puns, and math, and paradoxes, and big toothy grins, and winks directed at the fourth wall, so what's not to like? I think Ian does a good job of describing and explaining all the spaces, and why they're all cool. If I had one complaint, it would be that there aren't enough pictures. Actually, I do have that complaint. A book about geometries should have more pictures in it. But, besides that, it's a fun read, and it stays crazy enough to always keep you guessing. If you like bending your brain a bit, and you don't mind a good pun every once in a while (or a bad pun (or twenty)), then I think you should try Ian Stewart's Flatterland.

Boop. Just did a quick review. Two paragraphs. It doesn't even have a picture of the cover. Go read it, if you'd like.

Anyways, back to Flatterland. As the tagline says, it's like Flatland, only more so. And with a healthy helping of Alice in Wonderland to boot. Flatterland is set about a hundred years after Flatland, and follows the adventures of Victoria "Vikki" Line, a woman who finds her some-number-of-greats-grandfather's book, which is entitled Flatland. (Yes, they are actually the same book.) Anyways, Vikki reads Flatland, and in it finds instructions for summoning a being from Spaceland, in a way that is kind of hilarious.

So, Vikki summons someone from Spaceland. However, she gets a bit more than she bargained for. Instead of the stuffy, boring old Sphere from Flatland, she meets a loud, energetic, grinning creature known as the Space Hopper, who can travel through much more than just stuffy, boring old Spaceland. The Space Hopper equips Vikki with a Virtual Unreality Engine, or VUE, and takes her on a tour of all sorts of spaces and geometries, meeting many strange people along the way. They pay special attention to a strange place called Planiturth, and the fact that its inhabitants don't really know which space they're in.

Personally, I really liked Flatterland. I'm a big fan of puns, and math, and paradoxes, and big toothy grins, and winks directed at the fourth wall, so what's not to like? I think Ian does a good job of describing and explaining all the spaces, and why they're all cool. If I had one complaint, it would be that there aren't enough pictures. Actually, I do have that complaint. A book about geometries should have more pictures in it. But, besides that, it's a fun read, and it stays crazy enough to always keep you guessing. If you like bending your brain a bit, and you don't mind a good pun every once in a while (or a bad pun (or twenty)), then I think you should try Ian Stewart's Flatterland.

Labels:

friendship,

humor,

numbers,

SCIENCE,

time travel,

travel log

Flatland

Flatland, by Edwin A. Abbott, is a memoir written by one A. Square, who inhabits the two-dimensional universe known to us as Flatland. The first half of the book is about Flatland itself, and the lives of the people inside it, who live in a strictly ordered society where social class is determined by the number of sides you have. Women, all of which are lines, have the lowest status (even though they are technically really thin quadrilaterals). There's also this freaky thing where kids are beaten into being more regular, and color is not allowed, and it's kind of terrible.

The second half of the book is about A. Square's experience of being visited by a Sphere from Spaceland, which has a third spatial dimension. As A tries to wrap his head around the fact that there can be a third dimension, the reader gets to try to thing about what a fourth dimension could mean. The Sphere also takes A through the first and "zeroth" dimensions, which is fun. Then the Sphere takes A back home, at which point A is promptly thrown in jail for being a lunatic. If you like dystopias and/or thinking about higher dimensions, then Flatland is a book you might like.

The second half of the book is about A. Square's experience of being visited by a Sphere from Spaceland, which has a third spatial dimension. As A tries to wrap his head around the fact that there can be a third dimension, the reader gets to try to thing about what a fourth dimension could mean. The Sphere also takes A through the first and "zeroth" dimensions, which is fun. Then the Sphere takes A back home, at which point A is promptly thrown in jail for being a lunatic. If you like dystopias and/or thinking about higher dimensions, then Flatland is a book you might like.

Friday, February 10, 2017

Our Mathematical Universe

Our Mathematical Universe is about big questions: Why are we here? What made it all? What's it all made of? Where did we come from? Where will we go? Where did we come from, Cotton Eye Joe? and so forth. More specifically, it is about Max Tegmark's answer to all those questions.

Tegmark takes us on a tour of the extremes of physics, from the epic scales of our entire universe to the smallest scales of atoms and space. The part about cosmology and the beginning of the universe is especially good, because Tegmark has personally worked with the data from satellites investigating the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation. He also talks about the possibility of multiverses, and identifies four different "levels" of multiverse. I like that he stresses that there is no such thing as a "multiverse theory" in physics; multiverses are not a theory, but a prediction of other theories.

Then he talks about his idea that, in the end, the entire universe is a mathematical object. He makes quite the compelling case for the idea, essentially arguing that for physics to mean anything it has to be true, but in the end he didn't convince me. It's kind of a nice idea, though. A good effort. Anyways, if you'd like to see the structure of the entire book, it's something like this:

Yep. That's taken right out of the book. Tegmark did some of my job for me. Nice of him.

When Tegmark says "my quest for the ultimate nature of reality," he means it. The book is about his quest. Our Mathematical Universe could equally accurately be called Max Tegmark is a Nerd, although I doubt that would sell quite as well. The book is filled with personal anecdotes and little asides, which I think adds to it a lot. Then, of course, there's the whole "reality is math" thing that he believes. Still, he's an interesting person with interesting ideas, so it's fun to go on the "quest" with him. He certainly kept me to the end, at least. If you're also interested in the big questions about what it's all about, and you don't mind having a friend along for the ride, then you would enjoy reading Our Mathematical Universe.

Tegmark takes us on a tour of the extremes of physics, from the epic scales of our entire universe to the smallest scales of atoms and space. The part about cosmology and the beginning of the universe is especially good, because Tegmark has personally worked with the data from satellites investigating the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation. He also talks about the possibility of multiverses, and identifies four different "levels" of multiverse. I like that he stresses that there is no such thing as a "multiverse theory" in physics; multiverses are not a theory, but a prediction of other theories.

Then he talks about his idea that, in the end, the entire universe is a mathematical object. He makes quite the compelling case for the idea, essentially arguing that for physics to mean anything it has to be true, but in the end he didn't convince me. It's kind of a nice idea, though. A good effort. Anyways, if you'd like to see the structure of the entire book, it's something like this:

Yep. That's taken right out of the book. Tegmark did some of my job for me. Nice of him.

When Tegmark says "my quest for the ultimate nature of reality," he means it. The book is about his quest. Our Mathematical Universe could equally accurately be called Max Tegmark is a Nerd, although I doubt that would sell quite as well. The book is filled with personal anecdotes and little asides, which I think adds to it a lot. Then, of course, there's the whole "reality is math" thing that he believes. Still, he's an interesting person with interesting ideas, so it's fun to go on the "quest" with him. He certainly kept me to the end, at least. If you're also interested in the big questions about what it's all about, and you don't mind having a friend along for the ride, then you would enjoy reading Our Mathematical Universe.

Friday, January 20, 2017

What's Math Got Do Do With It?

Jo Boaler's What's Math Got To Do With It? is about math education. It might surprise you to know that I am interested in this subject. Then again, it might not. I think the best audience for this book is mostly people like me, who are interested in teaching, and maybe parents who want to help their kids learn math.

In other words, What's Math Got To Do With It? is exactly what it says on the cover: it's a book about how teachers and parents can transform mathematics learning and inspire success. It mostly focuses on math teaching in the U.S. and the U.K. and it presents actual research studies on what works and what doesn't. It is well-written and clear, and gives strategies with concrete examples.

In conclusion, if you are a how teacher or parent who wants to transform mathematics learning and inspire success, then you should read What's Math Got To Do With It?.

In other words, What's Math Got To Do With It? is exactly what it says on the cover: it's a book about how teachers and parents can transform mathematics learning and inspire success. It mostly focuses on math teaching in the U.S. and the U.K. and it presents actual research studies on what works and what doesn't. It is well-written and clear, and gives strategies with concrete examples.

In conclusion, if you are a how teacher or parent who wants to transform mathematics learning and inspire success, then you should read What's Math Got To Do With It?.

Sunday, January 08, 2017

Prime Obsession

Prime Obsession is written by John Derbyshire, who also wrote Unknown Quantity. Like Unknown Quantity, it is a book about the history of math. Specifically, it's about the Riemann Hypothesis, how it came to be, and what it actually means.

The Riemann Hypothesis is the greatest unsolved problem in mathematics, at least according to the subtitle. It makes a statement about a function (which is described in the book) that has a deep connection with the prime numbers (which is also explained in the book). If you're the kind of person who reads math books, then you've likely already heard of the Riemann Hypothesis. It's one of the six remaining unsolved Millennium Prize puzzles, so proving it to be true or false will make you a million dollars richer.

Prime Obsession is divided into two parts. The odd-numbered chapters are math-heavy, and the even-numbered chapters focus more on history. This is done so that a reader who's just into math can only read the odds, and a reader who's just into history can only read the evens. I don't really like this split; I preferred the structure in Unknown Quantity, where both areas were present throughout the entire book. The split between the chapters removes the interesting math from the interesting stories of the mathematicians. As a more math-leaning person, I found the even chapters a bit slow. Because the people and their stories were not connected with their ideas, a lot of the people become forgettable to me.

All in all, though, I did like the book. Derbyshire explains everything clearly and takes time to ensure that the reader understands what's going on. This is the first source I've found which explains the zeta function's connection to the primes in a way that's clear and satisfying (although it does take a while to get there). I also like that, when Derbyshire does skip a few steps in the math, he takes a moment to explain that and why he is doing so. If you're curious about what this whole "Riemann zeta" business is about, then Prime Obsession is the book to read.

P.S.: You should also watch this video by 3Blue1Brown, which is about visualizing the zeta function. You can consider it a supplement to chapter 13, or you can just watch it because it's pretty.

The Riemann Hypothesis is the greatest unsolved problem in mathematics, at least according to the subtitle. It makes a statement about a function (which is described in the book) that has a deep connection with the prime numbers (which is also explained in the book). If you're the kind of person who reads math books, then you've likely already heard of the Riemann Hypothesis. It's one of the six remaining unsolved Millennium Prize puzzles, so proving it to be true or false will make you a million dollars richer.

Prime Obsession is divided into two parts. The odd-numbered chapters are math-heavy, and the even-numbered chapters focus more on history. This is done so that a reader who's just into math can only read the odds, and a reader who's just into history can only read the evens. I don't really like this split; I preferred the structure in Unknown Quantity, where both areas were present throughout the entire book. The split between the chapters removes the interesting math from the interesting stories of the mathematicians. As a more math-leaning person, I found the even chapters a bit slow. Because the people and their stories were not connected with their ideas, a lot of the people become forgettable to me.

All in all, though, I did like the book. Derbyshire explains everything clearly and takes time to ensure that the reader understands what's going on. This is the first source I've found which explains the zeta function's connection to the primes in a way that's clear and satisfying (although it does take a while to get there). I also like that, when Derbyshire does skip a few steps in the math, he takes a moment to explain that and why he is doing so. If you're curious about what this whole "Riemann zeta" business is about, then Prime Obsession is the book to read.

P.S.: You should also watch this video by 3Blue1Brown, which is about visualizing the zeta function. You can consider it a supplement to chapter 13, or you can just watch it because it's pretty.

Thursday, January 05, 2017

Elliptic Tales

You will probably not enjoy Elliptic Tales, by Avner Ash and Robert Gross. I enjoyed it a lot, but I suspect I’m in the minority on that. You see, Elliptic Tales is by far the most math-intense math book I’ve read. In my opinion, this is a good thing. However, the whole thing might be a bit… daunting to someone who is not actually into math.

Let me back up a bit. What is Elliptic Tales about? Well, Elliptic Tales is a book which will explain to you what exactly the Conjecture of Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer (or BSD Conjecture for short) is. This might be of interest because the BSD Conjecture is one of the six remaining unsolved Millennium Prize puzzles, meaning there is a reward of one million dollars for whoever proves it. To me it's of interest because I'm a nerd, and I want to know what kinda stuff is being worked on in math right now.

The thing is that the BSD Conjecture involves a lot of preparation, and although Ash and Gross do a wonderful job at explaining things, there are some patches in which everything is confusing for a bit. My advice for these parts is to just read on for a bit. Sometimes, Ash and Gross mention concepts that they don't actually introduce until the next paragraph, or even later than that. Trust me when I say that it mostly makes sense in the end. Also, use the glossary. It helps.

I think my favorite parts of Elliptic Tales are the ones in which they are teaching about something else. This is the first source I've found which explains projective geometry well, and some of the earlier stuff with generating series is cool enough to create a formula out of. They say you can skip Part 1, which deals with the degree of a polynomial, but I had a lot of fun reading it. Also, they reference that part later in the book, so if you haven't read it you feel a bit cheated and left out. How do I know how this feels, given that I did read Part 1? Because they also reference their previous book, Fearless Symmetry, and that's how it makes me feel.

So, I really enjoyed the book, because it taught me a lot. However, I realize that this isn't that big a selling point for most people. If you don't really like math, then stay away from Elliptic Tales, and instead read Things to Make and Do in the Fourth Dimension. If you do really like math, and are excited about learning math, then read Fearless Symmetry, so that you can later fully enjoy Elliptic Tales. And never, under any circumstances, read Bridges to Infinity. I think that about covers everything. Until next time!

Let me back up a bit. What is Elliptic Tales about? Well, Elliptic Tales is a book which will explain to you what exactly the Conjecture of Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer (or BSD Conjecture for short) is. This might be of interest because the BSD Conjecture is one of the six remaining unsolved Millennium Prize puzzles, meaning there is a reward of one million dollars for whoever proves it. To me it's of interest because I'm a nerd, and I want to know what kinda stuff is being worked on in math right now.

The thing is that the BSD Conjecture involves a lot of preparation, and although Ash and Gross do a wonderful job at explaining things, there are some patches in which everything is confusing for a bit. My advice for these parts is to just read on for a bit. Sometimes, Ash and Gross mention concepts that they don't actually introduce until the next paragraph, or even later than that. Trust me when I say that it mostly makes sense in the end. Also, use the glossary. It helps.

I think my favorite parts of Elliptic Tales are the ones in which they are teaching about something else. This is the first source I've found which explains projective geometry well, and some of the earlier stuff with generating series is cool enough to create a formula out of. They say you can skip Part 1, which deals with the degree of a polynomial, but I had a lot of fun reading it. Also, they reference that part later in the book, so if you haven't read it you feel a bit cheated and left out. How do I know how this feels, given that I did read Part 1? Because they also reference their previous book, Fearless Symmetry, and that's how it makes me feel.

So, I really enjoyed the book, because it taught me a lot. However, I realize that this isn't that big a selling point for most people. If you don't really like math, then stay away from Elliptic Tales, and instead read Things to Make and Do in the Fourth Dimension. If you do really like math, and are excited about learning math, then read Fearless Symmetry, so that you can later fully enjoy Elliptic Tales. And never, under any circumstances, read Bridges to Infinity. I think that about covers everything. Until next time!

Tuesday, January 03, 2017

Romeo and/or Juliet

Romeo and/or Juliet is a choose-your-own-adventure book by Ryan North. It has not only one, but several plots, as is typical of a choose-your-own-adventure book. Because of this, I can't really do a plot-focused review, and so I have been putting this off for like two months, because I don't really know what to say.

Romeo and/or Juliet is funny. It makes fun of the original Shakespeare work, pointing out the silly parts of the story and usually replacing them with even sillier ones. The narrator is more of a character than most of the characters, and likes to make anachronistic remarks. When reading, I pictured the narrator as a flying red fairy. You can also do this, if you want.

Well, that's all I've got. Next time, remind me to review a book with a stationary topic. If you like dumb laughs and/or Shakespeare, then you should read this book. Or, I guess I mean you should play it. Interact with it. Read sections of it, and then at the end of those sections make a decision between the offered choices and turn to the appropriate section, and then repeat this process until you get an ending.

See, this is why I had trouble.

Romeo and/or Juliet is funny. It makes fun of the original Shakespeare work, pointing out the silly parts of the story and usually replacing them with even sillier ones. The narrator is more of a character than most of the characters, and likes to make anachronistic remarks. When reading, I pictured the narrator as a flying red fairy. You can also do this, if you want.

Well, that's all I've got. Next time, remind me to review a book with a stationary topic. If you like dumb laughs and/or Shakespeare, then you should read this book. Or, I guess I mean you should play it. Interact with it. Read sections of it, and then at the end of those sections make a decision between the offered choices and turn to the appropriate section, and then repeat this process until you get an ending.

See, this is why I had trouble.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)